Day in the life of

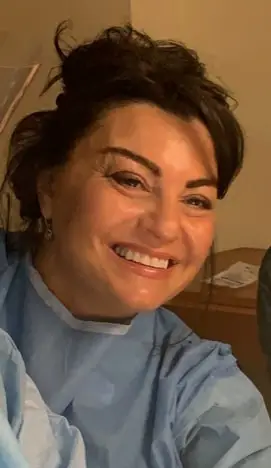

Licensed Psychologist – Stephanie Olarte, PhD

I’m a licensed psychologist and I specialize in children and families. I work in community mental health and in private practice. My speciality is, broadly speaking, the children who never behave. Lots of therapists out there think they work well with children, but really, they only work well with children who are even-tempered or well-behaved. My passion is working with the kids who are “out of control” according to their teachers and parents. In short, I have an unrelenting enthusiasm for a child who is on the verge of a meltdown.

My typical day

My favorite part of my job is that the “typical” day will actually vary from one day to the next. There’s some routine and predictability, but Tuesday can look very different from Monday, and as someone with ADHD, I personally thrive under these conditions. My job is the opposite of monotonous.

I engage children and teens in therapy through play. This means that we are often playing while we get to know each other or eventually work through the issue that brought them to therapy (for my clients, it’s mostly ADHD, depression, and explosive behaviors).

When I work virtually, I usually have an online board game or other online play platform (e.g., Roblox or Minecraft) that is the focus of our session.

When working in person, my personal favorites are pretend sword fighting, coloring, or building Legos. I tailor each appointment to the child’s main concern. If they’re struggling with low self-esteem, we’ll plan and execute an awesome Lego project together. If they’re hyperactive or explosive, we’ll start with an intense round of pretend sword fighting and end with some deep breathing exercises and then some coloring to help them calm their bodies.

When doing family sessions, I try to provide an age-appropriate activity for the kids that is also engaging for the parents. Sometimes this means playing with shaving cream on a table, or it can be a board game that involves talking about our feelings.

I also do a lot of virtual parent sessions. During these meetings, I get to be in the comfort of my home office while I talk to parents about their kid’s behavior that week, and we spend time exploring the child’s emotional inner world. This can be intense, but watching the outcome is actually quite fun because I get to see the spark reignite between the parent and child (who are often very frustrated with each other by the time they come to me).

Pros

My job is deeply fulfilling. Some of my best moments have been watching kids develop the skills needed to reflect on their own behavior and think about ways to improve (e.g., slowing down when they become hyperactive, take better care of their sleeping habits, make amends with parents and teachers when appropriate). I also love watching families re-connect through joyful activities, which does wonders for kids’ mental health.

Cons

When working with children and teens, you must work with the “team” of adults around them as well, otherwise you’re not going to get very far. This means meeting with teachers, and meeting with parents or other caregivers in the home. Sometimes these other adults can be uninvested or otherwise difficult to work with. Sometimes this looks like teachers who refuse to answer a simple behavior questionnaire, or parents who frequently cancel or forget parent meetings. When this happens, there’s a chance that the “team” will engage in behaviors that undo a lot of the hard work the child has done in therapy. Or worse, parents will see that progress isn’t made “fast enough” and they pull the plug on therapy prematurely, which can actually cause more damage.

Advice for students interested in becoming a psychologist

Understand that becoming a psychologist is a massive financial undertaking. You will not only incur the expenses of the education itself, but you will also have to pay to obtain clinical hours, work for free, and also feel the repercussions of lost income during the years that you’re not working full time. Also, the job market can be hostile for psychologists (e.g., low salary, or preference for Master’s level clinicians due to lower salary). This will often require you to have some basic business skills because it’s likely you will have to venture into your own private practice in order to recoup your initial investment (i.e., pay back your student loans). I really wish someone had sat me down to discuss finances before I started my PhD program. In undergrad I was fortunate enough to get through it without a single student loan, but the pendulum swung in the opposite direction in grad school. It wasn’t just tuition, supplies, and housing, but also having to work for free for more than two years to obtain my clinical hours. I also had to move across states twice (sadly, this is not uncommon). I was the first in my family to get a college degree and I often surrounded myself with others who also had no clue what a huge financial responsibility this was. I pursued a doctorate under immense pressure from my family, but in the end, I’m the one paying these student loans, not them. Mind you, this happened even though I had some generous financial aid packages aimed at first generation college students.

I’m really glad that during my undergrad years I worked in research labs to get a better sense of how research is conducted. This also made me a more competitive candidate for PhD programs. I never went into academia but I still consider myself a well-rounded professional, which was my goal. Working in research labs along the way definitely helped.

If you’re a first-generation college student, look for mentorship programs. I was privileged to get into the McNair Scholars program in undergrad and that made a huge difference. Surround yourself with other students who are fighting the same fight. They’re not your competition, they’re your comrades. This attitude will serve you well as a mental health professional as well.